The new documentary Amy points fingers at several people close to the soul singer as culprits in her death. We ask director Asif Kapadia: Who is really to blame?

SHAUN CURRY/AFP via Getty

It’s the unfortunate circumstance of the legacy of Amy Winehouse: The death may be more famous than the life.

Amy, the new documentary from filmmaker Asif Kapadia (Senna), intimately revisits that life—the God-given talent and incandescent soul—as a crucial reminder of just how tragic the hard-living star’s very public battle, and at times even embrace, of addiction was.

Collated using home video and archival footage shot by friends, TV stations, and, most upsettingly, paparazzi, the film is narrated with interviews from those who were by Winehouse’s side at various stages of her meteoric rise and shocking fall.

It’s an effective narrative trick, telling Winehouse’s story using Winehouse as the de facto storyteller. As we all too quickly forget, few artists in the past decade were as captivating and effortlessly watchable as her.

Framed around Winehouse’s songs and the stories the lyrics tell, Amy doubles as detective work by way of documentary, spurned by mass outcry. Ever since Winehouse’s death in 2011, fans have demanded to know, or at least better understand, how a person with so many people around her at all times could succumb to addiction in such a cruel and operatic way.

Why wasn’t she helped? Why did she die? The whole world knew what was going on. How could we have let her?

Who killed Amy Winehouse?

“This just happened the other day and no one’s really talked about it,” Kapadia tells me. “Nobody’s given me any answers. And it transpired as I was making it, nobody knew. There was no one person who knew everything.”

The access Kapadia was granted for the film is astonishing, accruing over 100 interviews, including her childhood friends, her ex-husband Blake Fielder-Civil, her mother, and her father. Still, her father has since publicly condemned the film—saying that Kapadia and his producers “should be ashamed” of themselves—making one wonder how he coaxed them into such candid participation in the first place.

What outside forces, perhaps motivated by greed as her career became unfathomably popular, may have therefore been complicit in Winehouse’s death is the film’s key exploration.

The role of Fielder-Civil, her aider and abetter in the throes of a drug-fueled romance, is explored. Mitch Winehouse, Amy’s father and the film’s most vocal critic, certainly doesn’t come out unscathed—perhaps explaining his displeasure with the finished product.

When it is revealed that producer Nick Shymansky, who Winehouse is singing about in “Rehab,” tried to get the singer treatment in 2005, Mitch is portrayed as believing it was unnecessary. (A position he has since refuted.)

“It’s all there. We just didn’t pay attention. We didn’t read the songs. We didn’t pay attention to what she was saying.”

There’s a particularly unsettling sequence in which Mitch follows his daughter to St. Lucia, where she had retreated to free herself from the temptations that London brought her, but brings a camera crew with him to document his trip. What was his end game? Did he put fame and opportunity above his daughter’s health?

And there’s the transfixing scene that shows Winehouse wide-eyed waiting to find out if she won the Grammy Award for Back to Black, only to follow her glee with a confession to a friend: “This is boring without drugs.” There’s an unshakable urge to point fingers and place blame, and Amy certainly presents its fair share of culprits—the least of which is the doomed singer herself.

But the film also raises the question of our own culpability, the culture that consumed with rabid insatiability every shot, footage, and news story about her demise, as it was documented in real-time by the now-villified paparazzi. Are we as bad as them? And what about the responsibility of using and paying for paparazzi footage in a film about a star whose death may be owed to their pursuits?

Amy Winehouse’s death, all these years later, is still clouded with questions. So we grilled Kapadia, as much of an expert on the demons in Winehouse’s life as any at this point, for answers.

Did you think it was your mission to find answers?

Maybe my mission was to ask some questions that I don’t think anyone had asked. It became clear that nobody was around for her entire story. You realize that this person was around for this period. And this person was around for this period. But no one was around the whole way. So she compartmentalized her friends. And I talked to them and would say, “I met this other person” and that friend would say, “Never heard of them, they’re just a hanger-on.” But then I would talk to them and it would be clear that this person really liked her and cared about her and was around for quite a period. But Amy didn’t tell them that each other existed, and they never met. And the people who did know of one another didn’t get along. Therefore they were never able to get together and get past their own issues to help her.

The compartmentalization—because of that there was a circle of people very present in her life at the worst time, the time right before she died. Because of that, it appears they share blame in what led to her death. How much of that blame is deserved, and how much of that is them just being around?

Who are you referring to?

The promoter-turned-manager (Raye Cosbert) who booked those disastrous late-career dates, when she was in such bad shape and maintained that it was her idea to do them and that she wanted to perform, but then there was the very pointed quote about her being passed out and actually having to be carried onto the plane—hinting that she did not want to perform. And then before that was Blake and her father. Those three, specifically.

Right. That, and all the above. It’s such a complicated story. She’s a very complicated girl. It was everything. That’s what we find out. I think it did start very young. You just add another thing on and add another thing on and at some point it’s going to drop. Definitely, the team around her made decisions that I think didn’t make sense. Asking them, they would say that they thought the best thing was to keep her busy, because if she’s alone in the room that wouldn’t be good. But I think there were opportunities earlier on when they could’ve changed things or stopped things or sought help, proper long-term help. It was a lot of short-term fixes.

Two sequences were particularly damning of people. One is the one just mentioned about being carried out to go on tour. The other is the father’s trip to St. Lucia. I went in as an audience member, and came away thinking these are two people who share a lot of the blame in this.

One of the natures of making this style of film is that you do a lot of research. I spoke to over 100 people, and you find out what’s going on.

I imagine you wouldn’t portray those events in that way if it wasn’t the case.

Yes. Then you find the visuals that this is going on, so you can show it. Honestly, then you have to find the essence of the story. There were a lot of incidents. There were a hell of a lot of incidents like that. You have to say I’m just going to show one. And there were more. It went on for a long time.

Audiences might go into this film hoping to be able to point a finger and say that’s a person who did it. As a filmmaker, are you weary of not doing that yourself? In these interviews not saying it was one person or another?

I don’t want to point the finger at anyone in particular because I think there’s a lot of elements that come together. It’s all to do with self-esteem much earlier. It’s all to do with the idea of family. It’s all in her lyrics. She says it in her voice. She says what happened in “Rehab.” “Rehab” is basically a documentary song about an incident about her first manager. Her first manager tried to take her to rehab and she said no, I won’t go. To me, the more she said no, like a child, the more she says no the more she means yes.

So she was in a way crying for help?

It’s all there. We just didn’t pay attention. We didn’t read the songs. We didn’t pay attention to what she was saying. I think all of those incidents are quite difficult. But the get out is just read the songs and lyrics and understand every clue that’s laid out there for us. The structure of the filmmaking was actually that we started with the songs. And once you talk to a few people, you realize it’s all in there. I just need to unravel each song. It was like a bad detective movie. “Who is she talking about here?” “Who is this person?” “What is that incident?” “Where did this happen?” And then you’d go and find the person and be like, “That’s about you, ohhh. Right. I get it. OK. It makes perfect sense.” Then they would tell you what’s going on at the time.

Was it hard to get these people to open up?

It was really weird and unusual and heavy. There were a lot of tears. There was a lot of fear. A lot of people were afraid. A lot of people said, “Look, this film is never going to come out. You’re never going to make this movie.” I was like, what do you mean? Journalists I spoke to said they had stories that were not printed. There was a lot of sense that we were not going to be able to do it. But we felt either we make the film that has to be made, or we don’t make it all. We can’t do that whitewash film.

Do you think people you spoke to were expecting a whitewashed film? You spoke to her family, who have since been vocal about their displeasure.

Not the whole family.

The father has.

Yes.

You convinced them to participate in the beginning though. What happened? How did you convince him to speak? He said the things that he said, but now he’s displeased.

Yeah, I know. The way the film begins is that you have to have everyone on board. You can’t have a movie about a musician if you don’t have the music. You need the music and the publishing and you need the label and you need the estate. They all approved the film and they approved us. They had seen the previous film, Senna. And so I went into the meeting and said it’s only worth doing this if we do it properly. Everybody knows the ending. We all know. We know two things: She was a singer and she died from something. Most of us think it was drugs. Well, it is drugs. It’s alcohol. So that was the given.

We just made it very clear that we’re going to talk to everyone. We have to talk to Blake. We’re going to talk to her friends. And people were like, “Oh, we’d rather you didn’t. At one point we got a call, “Why are you talking to these people?” We were like, we made it very clear to everyone that it’s only worth doing if we do it properly. James Gay-Reese, the producer, will say that he was asked by the label to make the film and make it warts and all. And so we just reminded everyone what was said to us initially. And then we got to make the film.

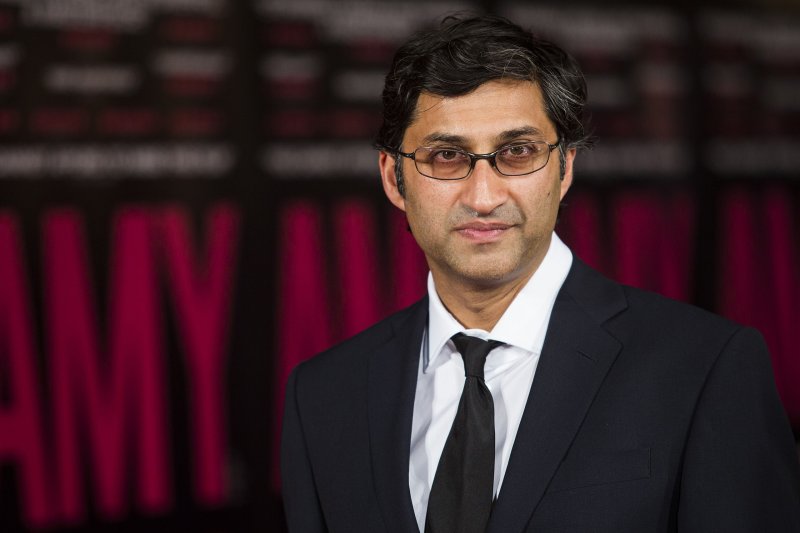

‘Amy’ director Asif Kapadia. (Jack Taylor/AFP/Getty)

That’s the root of my question. Why would her father agree to participate in the interviews knowing what he must come off like, and then in the end act shocked about how he came off? You’re not him, I understand. But what happened there?

I think—really there’s a lot of deep psychological stuff going on here, man. I guess the way I put it is that the film’s called Amy and it’s about her. I’m on her team. I’m on her side. I wanted to show what a weird, complicated person she was—brilliant person, but complicated—and what a complicated situation she found herself in. And hint to everyone around that they weren’t making decisions that were best for her at that point. It was best for them. That I think sums it up. That’s the issue still. They’re not necessarily thinking of her. They’re thinking of themselves. That’s the way it’s always been. That’s one of the challenges, maybe, of being her. There was always another presence that she desperately wanted around, and they also made it all about them.

Spending so much time in her life and getting so deep especially into the parts of her life where she was so troubled, do you think she was ever savable?

The people I’ve spoken to and the doctors and people in that world and experts and friends have all said the earlier you do it the more of a chance you have—the earlier you get in there and try to help her before everything has kicked off. That’s where the incidents—and there’s more than one—that form “Rehab” might have given a better opportunity to save her than after Serbia. And even then they tried. Then people said, a lot of people I’ve spoken to who are in recovery saw that and said, “She’s going to die.” “I’ve been there, let me talk to her.” There are people who have helped a lot of famous rock stars who said she’s going to die, just give me five minutes. I don’t know why they never got their five minutes. So that’s right at the end.

So there was an opportunity there?

At the beginning was the opportunity. She was a brilliant, intelligent person, a tough character and stronger than everyone in one way, but weaker than everyone else in another way. And I think that’s why people found it difficult to get her to do what they wanted to do. I’m not an expert, but there’s an old-fashioned thing where they say you can’t force people into treatment. They have to do it themselves. But then other people say, “Yeah, but you do that and then they die.” So there’s a point where you do have to force them. And earlier was the opportunity. The other answer away from that is that, I love the city, but she had to get away from London. She had to go somewhere else. And I don’t mean go to live in California. Personally, go to India. Go somewhere people literally don’t know who the hell you are.

She seemed healthier in St. Lucia.

Yes, that was a good place. Yes, and but. She did like it there. But the place she was staying, that’s where it went from drugs to alcohol. It was a free bar, and nobody says no because it’s a five-star hotel and people just give you what you want. So she just switched to a more dangerous drug, which is alcohol. Or switched back to it, because she was always from a very young age drinking. In St. Lucia she was happy, but unfortunately she did drink. For me, it was going back to London after that.

Why did going back to London ruin her?

She was cleaned up a little, but there was always this pressure of delivering another record. So there are a couple of things. One is that if she didn’t have to follow up Back to Black with another hit record, she may have been better. I’d have liked her to experiment with, like, a hip-hop record or a jazz record that sold nothing and destroyed her in one way, but freed her in another way. Failure is a really good thing in the long term. If you have huge success early on in any career it’s really hard. What do you follow that up with? She loved to create. Just make something. It doesn’t matter! Make an in-between album and then go live in India for a bit and realize you’re actually a tiny part of the whole universe. The world doesn’t revolve around Amy Winehouse if you get away from Camden.

It was a pleasure to see all the early clips of how talented she was, because so much of that gets lost in the narrative of Amy Winehouse, the tragic death. But I also wonder whether you were ever concerned about glorifying her too much.

I don’t know—I just like her! I liked being around her. She was really funny. Intelligent. Beautiful. Amazing eyes. You just think, god, she was cool. I heard this from a lot of people. That’s the person they would talk about and would be like, I just don’t see it. I don’t get it. She seems so cold and harsh. And then to them she was the most giving person and made everyone think they were the most important person. Everyone I met, wherever they were, said they were her best friend. She had so many best friends, and yet felt so lonely all the time. The person in the beginning they kept going on about was the real Amy. For me, once we found that footage I realized we’ve got a real movie. Because other than that, you’re thinking, “I’ve seen a hell of a lot of bad performances.”

Yes. And unfortunately the bad performances are the ones we all remember.

She never sang the same way twice. It used to wind the people at the record company up. It wound the bookers up, because people would be expecting the record and then she’d perform it in a different way. The problem was she wasn’t a pop star. “Just show up and sing the bloody record.” Or “we’ll just press play and you dance.” She didn’t fit into that thing they wanted her to be. As Nick, her producer, would say, now all pop stars and rock stars and hip-hop artists, they’re like CEOs. They all want to run corporations and they’re super professional and always arrive on time. She was old school—didn’t give a fuck about that stuff. Not interested. But that didn’t fit in with what she became. Back to Black became too big. She sang to herself all the time. Even her mom at one point says, “Ugh, Amy, shut up.” She was just constantly singing. Then the problem is that singing becomes the problem so in the end she doesn’t sing. To end it all, the only thing she could do was not sing—Serbia, which you must have seen at the time.

Everyone saw the Serbia footage. The whole world saw it.

The whole world. Also, she became one of the first people to become famous on social media. So it was everywhere. In the ’70s someone does a bad concert and you might read it. But this, everyone saw it. They commented on it. So that turned into like an act of defiance, where she was like I’m going to do this on purpose.

It’s hard to see the movie and not find the paparazzi to be vile and despicable. And yet the movie couldn’t exist without footage from the paparazzi. It’s an interesting tension in the film.

It’s context as well. I was always fully aware of the question of, “What am I doing here?” But my job was to change the story in the best possible way using the tools at hand. She did exist through that lens. But the answer to that starts a bit earlier. It starts with photographs Julia and Lauren [her childhood friends] take when they’re hanging out and staring into the lens. And then Nick turns up and she’s talking to him into the lens. Then she’s performing and looking in the camera. Then it changes when she’s married and Blake starts filming her. Then she’s on TV and the whole way through it’s about Amy and the lens.

Then it gets darker, that’s when she gets married and there’s the Terry Richardson shoot and all of that. Again, she’s talking to us through the camera. And later on the camera becomes a negative force. It becomes violent. She fights with the camera, the paparazzi. I thought that’s what I was more interested in, that journey overall. And part of that process was that there was a point when she only existed through the paparazzi photographs. So for me, it just makes sense that we have to use it. Because that’s the story. And it’s visceral because we use it. If I just had a talking head saying, “And the paparazzi photographing her was horrible!” So? Tell me what you don’t know. The difference here is that you feel it.

It’s necessary. And it is powerful.

We’re all aware that the media was going to ask about this. Of course I thought about it. But the bigger picture is that I wanted to make the point that this was not a good existence and we’re all consuming it. For me it was not a difficult decision. It was the right thing to tell the story.

Did you pay for the paparazzi footage?

Of course. You pay for any footage you use.

Watch:

Amy

The story of Amy Winehouse in her own words, featuring unseen archival footage and unheard tracks.