Say what you will about John McAfee — and people say a lot of nasty things — but he was one of the first nerds to warn the world of an impending computer-security crisis, a pioneer whose paranoia served a legitimate purpose.

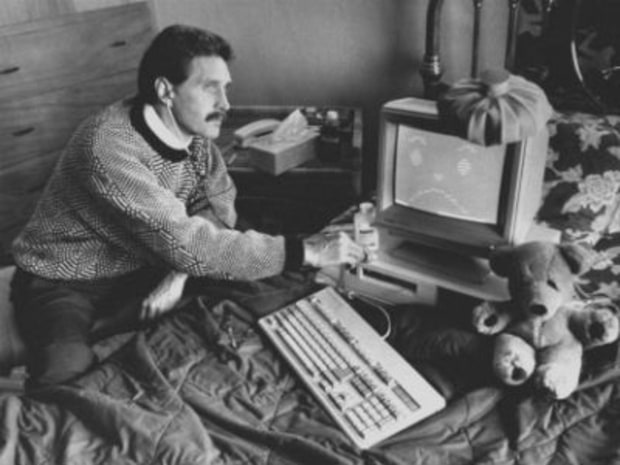

John McAfee in Tennessee in May. In the ’90s he made $100 million by creating the first computer antivirus software. (Photo: Chris Buck)

It has something to do with a schmear. The 70-year-old McAfee resembles an ocelot, with his striped and streaked hair. He is probably still a multimillionaire, but he chain-smokes generic cigarettes the way a toddler eats Goldfish crackers. He exhales, as a hawk circles above.

“All they eat is cream cheese,” McAfee says between phlegmy hacks. “Must be for the protein. I find cream cheese packets everywhere. Some of them are out-of-date.”

Inside, somebody named Bob writes down the license plate of every car that drives by the property. McAfee believes Bob’s brother is working for the cartel, but that’s really neither here nor there. McAfee scans the dirt for plastic.

“If there’s cream cheese, I know the cartel has been here.”

Say what you will about John McAfee — and people say a lot of nasty things — but he was one of the first nerds to warn the world of an impending computer-security crisis, a pioneer whose paranoia served a legitimate purpose.

Long before the Y2K freak-out, he — after stints as a computer programmer at Lockheed and NASA — built McAfee Associates out of his home in the late 1980s, creating an antivirus program for corporations before most companies knew what a virus was. At first, he gave it away to individuals, then he began to license it to companies. Oh, and he had the self-promotional skills of a young Johnny Knoxville. He transformed an RV into a Ghostbusteresque antivirus mobile unit, arriving in the parking lots of threatened firms. In 1997, he warned of the coming Michelangelo virus and claimed it would destroy whole corporations. It turned out to be just a computer fart in the wind. By then it didn’t matter. McAfee sold his shares in McAfee Associates for $100 million.

He headed into semiretirement, working on some projects — including a before-its-time chat program — and bugging the fuck out of people. He bought a sprawling property in Molokai and proceeded to take out newspaper ads pointing out drug houses. McAfee then sold his property, amid rumors he was going to develop it into condos. Neither act endeared him to locals. He moved to New Mexico and created an aircraft business, renting out ultralight planes that could swoop in and out of canyons. That ended in tragedy when his nephew and a passenger flew into a canyon wall. McAfee was recently found negligent in their deaths to the tune of $2.5 million. (McAfee claims they were shot down by a drug cartel hiding in the canyons.)

McAfee lives by the Liberty Valance credo: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” He moved to Belize in 2008 and, depending on his mood, told reporters that he was either seeking to create antibiotics out of natural herbs, developing female Viagra, or manufacturing bath salts, a synthetic hallucinogenic. (Regarding the last claim, McAfee later said he was just pulling the chains of reporters.)

What isn’t up for debate is that McAfee had a posse of teenage girls living with him. They were misfits, runaways, and troublemakers; one pulled a gun on him. (His stay in Belize is so notorious that there is a libidinous, perhaps insane, gun-wielding character living in Belize in novelist Jonathan Franzen’s upcoming Purity that bears a resemblance to McAfee.) Ask him what he was thinking when he decided to shack up with a harem one-third of his age, and McAfee will flash a devilish smile and say simply he was single and having fun. The “fun” took a sour turn in April 2012, when a Belizean SWAT team raided his island estate looking for criminal activity and shot and killed his dog. That November, his American expat neighbor was murdered by gunshot.

Considering his past run-ins with the government, McAfee feared a frame-up. He went on the run, causing a media frenzy largely created by McAfee himself, who allowed two staffers from the website Vice to tag along as he fled for Guatemala. This backfired magnificently when the Vice crew posted a picture of McAfee in hiding but forgot to scrub the geo data that pinpointed them to a Guatemalan resort. Oops! McAfee was arrested for entering the country illegally, and authorities considered deporting him to Belize. Guatemala eventually grew sick of the drama, didn’t press charges, and allowed him to head home to the United States.

Promoting his antivirus software in 1989.

That was more than two years ago. McAfee laid low for a while, sometimes literally: under cars to avoid his purported enemies. But he resurfaced earlier this year, touting new business partners and apps to fight off data stealers. He warned of security anarchy that would ruin families, governments, and perhaps Western civilization.

And that’s when I meet him. Tanned but hardly rested, McAfee is ready for his comeback. But things are different now. Once, McAfee was seen as a semidangerous rogue; now he has to prove he’s not just an eccentric sideshow. A half-decade ago, he posed for magazines on his beachfront estate surrounded by girls and guns. Now he is staying in no-tell Alabama motels while spreading his message, managing a mortal-coil-cutting cough, and living in rural Tennessee, not far from a casket store called Til Death Does Us Part. The question now is: Will anybody buy what John McAfee is selling?

John McAfee looks like an elderly man who has driven through the night while inhaling nicotine instead of oxygen. That’s because he has, motoring 313 miles from his Lexington, Tennessee, home to the main offices of his new venture, Future Tense Central, in Opelika, Alabama. Future Tense is located within Round House, which is basically a storefront with some cubicles for Web entrepreneurs taking advantage of the fact Opelika has one of the six fastest internet services in the country. For McAfee, he’s using that bandwidth to peddle two apps he says will keep you safe. There’s D-Vasive, which prevents malicious apps from infiltrating your phone’s vulnerable points — camera, WiFi, recorder — the minute you’re done using them, and D-Central, a program that ranks the risk of your apps from one to 100.

Some computer experts say this kind of protection is crucial, suggesting that your smartphone is as secure as a vacation cottage with a come on in sign posted on the mailbox.

“Your phone is no different than a house,” says Babak Pasdar, a security expert and CEO of ?Bat Blue Networks. “That house has doors designed to have people come and go, and windows designed to see out. The doors can be used to compromise the system and steal information or spy.”

Like any good salesman, McAfee says his apps are the only thing that can save you from the coming apocalypse.

“I can guarantee you, there are thousands of teenage girls taking showers right now with waterproof phones, texting, who are being watched by somebody,” says McAfee.

Maybe five years ago, McAfee would have been dismissed as a giant nut bag, but too many holes have been punched into our computer systems to dismiss him now. Last spring, thousands of emails detailing the petty personal thoughts of Hollywood’s dream makers were laid bare when Sony had its email system pried open for the world to see. The email lists of Adult FriendFinder and Ashley Madison, naughty services for men and women seeking extracurricular sexual shenanigans, were released on the Web. There are now rumors that China has wormed into the mainframes of Pentagon subcontractors.

With his wife, Janice, in Tennessee in 2014.

We no longer have the tools to judge the sanity of people saying paranoid things about privacy and security because so many things we would have written off as dystopian delusions have come true. Now we have to judge our nut bags on a case-by-case basis. Reality has caught up to McAfee’s paranoia.

An hour or two after his arrival, I’m sitting in his office as his wife, Janice, brings him coffee. His business partner, Tom Gusinski, a stoic middle-aged man, stands with his arms folded. Despite McAfee’s multicheckered past, Gusinski kept bugging him to join Round House, and his patience has been rewarded with D-Vasive and D-Central. He accepts McAfee as he is and probably wouldn’t even mind that John could not recall his last name in a later conversation.

Outside the door lingers a man with a pistol tucked between his shirt and waistband. It’s John Pool, McAfee’s driver and gofer, and a guy who accessorizes with no fewer than five handguns. He asks McAfee if he needs anything but is ushered out of the way when Gusinski brings in Round House’s youngest entrepreneur, Taylor Rosenthal, an eighth-grader. The kid’s idea is a chain of first-aid vending machines — think Redbox and Coinstar — that could be positioned at rock festivals and sporting events, or wherever drunken people gather. He’s skipped school today to meet McAfee, who is impressed. McAfee makes a joke about keeping Rosenthal on the premises in a cage.

“You’ll actually like it in the cage. We’ll put puppies in that cage with you every now and then.”

The boy looks confused, shakes McAfee’s hand, and retreats.

McAfee rubs his eyes and says he needs a nap. Before he goes, I ask him why he thinks people take such pleasure breaking into other people’s private lives.

“People are people,” says McAfee. “There is dissatisfaction in all of us. Some of us take out that dissatisfaction by attempting to ruin whatever you are attempting to do. This is a fact of life.”

That evening, I meet McAfee in the lobby of the Microtel, a budget motel whose name says it all. A fellow guest eats Doritos and watches the Weather Channel while the rain turns the Alabama red dirt into brown clay.

“I don’t have any credit cards or anything in my name, so we try to do things cheaply,” McAfee tells me as Janice sleeps upstairs. He’s letting her rest because tomorrow will be a long day: a dawn flight from Atlanta to Las Vegas, where McAfee is giving a speech before the National Association of Broadcasters, and then back on a red-eye. (Obviously, McAfee can’t overnight in Vegas for security reasons.) “If nothing is in my name, it’s harder to find me.”

McAfee insists he wants this story to be about his future and not his past, but he can’t help recounting prior glories. He explains that after his Belizean property was raided and his dog was killed, he gave all the cute governmental secretaries laptops, knowing their minister bosses would steal them. What they didn’t know, McAfee says, was, in order to find out why the government was targeting him, he had installed spyware on the computers, which fed him reams of information on bureaucratic malfeasance. (Despite numerous requests and promises, McAfee never provided any damning documents or any documents at all.)

“There was not a single word about me in the files,” he explains, sounding disappointed. “But everything else under the sun. Scary shit. I became addicted. I couldn’t stop looking.”

McAfee believes it was his discovery of Belizean corruption that eventually forced him to leave the country. Well, that and the murder of his neighbor, Gregory Faull, another American expatriate sunning his life away in Belize. McAfee admits that Faull was pissed about McAfee’s dogs roaming on the beach but says that he held no rancor toward the man. Faull was found dead of a single bullet wound on November 11, 2012. While the local police insisted they wanted McAfee only for questioning — 300 yards separated their properties — he hightailed it into the bush, eventually hooking up with Vice News and publishing online pieces proclaiming his innocence.

The Belizean government’s response was succinct: “John McAfee is extremely paranoid, even bonkers,” said Prime Minister Dean Barrow.

After Vice gave away his location, McAfee was arrested by Guatemalan authorities. As he tells it, McAfee was given his own cell, WiFi, and good food but still feared extradition to Belize. He suffered a heart attack while detained, and footage of his body being loaded into an ambulance received global coverage.

But that’s not what happened. According to McAfee, the Belizean government had only one more day to get the Guatemalans to deport him, so he faked a heart attack. He offers a mischievous smile.

“I fell on my face very authentically in the cell,” says McAfee. “I busted my nose, blood everywhere, and they took me to the hospital.” He magically recovered that afternoon and was soon sent to the United States.

Very little of this, of course, is verifiable, and even McAfee admits that he’s lied about his past before. Some of the lies are sort of genius. When Dateline did a piece on his life, he nearly convinced an NBC producer that he had a decades-old contract with former NBC head Dick Ebersol that he be described as “the nation’s preeminent security expert.” This was not true.

Not all of the lies have been of the yuk-yuk variety; many have been self-serving Machiavellian chess moves minimizing his wealth to make himself less appealing to lawsuits. In 2009, the New York Times ran a story about gazillionaires scaling down as a result of the recession, and McAfee was the star. “What I said was absolutely false,” says McAfee. “Because it made a great story. A guy at the top is now at the bottom. At the time, I owned nine mansions around the world that had not been sold.”

Who knows, maybe he’s lying about the lying. He excuses himself to wake Janice. A few minutes later, John Pool brings around a tricked-out truck raised three feet off the ground, resplendent with a siren and a blinding spotlight, to take us to a sushi restaurant for a Future Tense dinner.

“I took this in for service and someone broke into the garage and attached a control board to the grille so they could make us wreck,” says McAfee, as Pool and Janice nod in agreement. At dinner, McAfee throws back a half-dozen sake shots even though he’s been telling reporters for years that he doesn’t drink. He promises to show me the control board when we get back to Tennessee. (He doesn’t.)

On our way back to the Microtel, McAfee tells me he spent most of 2014 on the road, bouncing from Ireland to Scotland and then to the Southwest, fleeing, he says, the Sinaloa cartel. McAfee believes the Belizean government has hired the cartel to either a) kill him, b) capture him, or c) drive him bananas. (He offers no proof.) One afternoon, they pulled into an Arizona truck stop and Janice noticed a Ford F-150 pickup truck was trailing them. McAfee pulled out of the station, playing cat and mouse on single-lane roads with the truck. He remembers punching his Focus up to 120 miles per hour before the F-150 backed off. When I ask why the truck didn’t just run him off the road, McAfee smiles.

“He’s just doing a job. We are running for our life.”

As the sun comes up, McAfee, Janice, and I wedge into the last row of a Delta flight bound for Vegas. Across the aisle sits Andrew, a Future Tense assistant, and John Pool, who insisted we get to the airport two hours early because Janice was checking some guns.

“It’s probably a good idea,” reasons McAfee, simultaneously gobbling a croissant and a bag of chips. “A black woman with dreads and a past checking guns could raise some questions.”

Janice is a nervous flier. One of the reasons McAfee loves her, he told me once, is that she’s just as suspicious as he is. McAfee holds her hand until we reach cruising altitude, and she falls asleep. He then tells me how they met.

“After I got out of Guatemala, I was resting in Miami, and a woman came into a diner and offered to blow me for a hundred bucks,” says McAfee as he scarfs another croissant. “I was exhausted and told her, ‘No thanks, but if you’d like to cuddle, I’ll compensate you.’ ” The two began a whirlwind romance on the run, but first McAfee had to tell her pimp to bug off or he’d send him home in a body bag. (The only verifiable part of this story is that Janice was once a call girl.)

“I felt like I was a lost soul,” Janice told me later. “I felt like everyone had given up on me. I just didn’t know where to start to turn my home life around, and he’s been there for me. I don’t like to let him out of my sight.”

They briefly bounced around the U.S. and Canada in hopes of ditching their pursuers, but McAfee says they were unsuccessful. The couple eventually wound up in Portland, Oregon. Their secluded bliss ended in the summer of 2013, when the Belizean soccer team came to Portland to play the United States.

“The Belizean team had never played a game out of Belize,” says McAfee. He beckons the flight attendant to bring him a Jack and Coke. “A coincidence? I don’t think so. My sources told me 22 of them stayed behind after the game.”

In reality, Belize had been in the country to play the USA as part of the concacaf tournament, for which Belize had qualified for the first time. (A quick check later proved that the team had played many games outside of its nation.)

John McAfee with business partner Tom Gusinski in Alabama in February.

Shortly after the game, according to McAfee, Janice and John looked out the window of their Portland condo and saw a fleet of cars idling in the middle of the night. So they fled. “You see two police officers, a limousine, a black fucking garbage truck all in a line pull up — it’s a scary scene.”

He didn’t file a police report, and local media stories suggest in reality McAfee was evicted from his condo for lack of payment.

McAfee orders another drink and pulls out a scrap of paper for his speech this afternoon. He has a trick up his sleeve to demonstrate how vulnerable all of us are to data breaches. He takes my Android phone — which McAfee claims is the easiest phone to hack — and taps the Facebook app. He touches a few buttons and gets into the Permissions sections.

“This is what you have given Facebook license to do. Directly call phone numbers, read your text messages, take pictures and videos, record audio, approximate where you are, read and modify contacts, send emails without owner’s knowledge, modify calendar events, read contact cards, modify contents of storage.”

I confess to McAfee that I didn’t know I’d consented to all of this. He shoots me a contemptuous glare and polishes off drink number two.

“Because you didn’t bother to look,” says McAfee. “You’re like 99.99 percent of Americans. If they choose to get in the porn business, because they’ve taken hundreds of thousands of pictures of people doing sex acts, that’s their right to do so. And you can do nothing about it.” He cackles and pats Janice on the head. “But this is Facebook, for chrissakes, they’re not going to get into the porn business. You’re lucky.”

McAfee gives me an example of how easy it is to tap in to someone’s smartphone, most of which have the data capacity of a desktop computer. With some basic information and a guessed password, McAfee can now monitor all the echats and emails sent by Janice’s daughter, living in the Bay Area. He fears some of her online friends are not on the level.

“They’re just dirty old men,” says McAfee. “I do know the people she’s talking to are not who they claim to be. End of story. Now, do I, as a father, have a right to spy on my 13-year-old daughter? That’s the fundamental question.”

After four and a half hours, we descend into Vegas. Janice frantically taps McAfee on the shoulder and shows him her phone.

“I got a 1-800 call.”

McAfee sighs. He pops out the battery of her phone and pauses before reinstalling.

“Don’t call it back. That’s an easy way to trace our movements.”

Backstage at the Las Vegas Convention Center, McAfee and Andrew huddle and work their phones, setting up a stunt for 200 attendees of the broadcasters convention. I sit with Pool, a balding, white-haired man with a penchant for endless Southern-fried chatter and a devout belief in his boss. “He doesn’t go anywhere without me,” says Pool, blowing on his coffee. He won’t exactly say what he did before working with McAfee, but it involved a “connected” family in Chicago. “I know there are bad guys out to get him and it’s not going to happen on my watch. I don’t need sleep, I can watch all day and all night.” Pool makes a face and excuses himself. A few minutes later, he returns holding a napkin to his bleeding mouth. I ask him what happened.

“I had a tooth that was bothering me so I went outside and asked a construction worker if I could borrow a wrench.” He shows me an off-color fang that was in his mouth 10 minutes ago. Pool tosses it into the trash. He flashes a gap-toothed smile. “Now I can enjoy my coffee.”

It’s showtime before this can be fully processed. McAfee takes the stage. Andrew sits off to the side on a stool. McAfee asks for a volunteer from the audience who is willing to give him a personal phone number and the number of someone in a contact list.

A man takes the stage and gives him the number of his friend Katie. McAfee pushes some buttons on his phone and calls the man. It rings and the number comes up as Katie’s, but when the man answers he doesn’t hear Katie’s voice — he hears McAfee’s.

“What I did was a simple test called spoofing; I can make anybody look like they’re calling anybody,” says McAfee. “What I just did could be done by any 12-year-old boy. Our mobile phones have become the greatest spy on the planet.”

McAfee says he is going to dial Andrew from his phone. Andrew has an ordinary phone except for the fact McAfee has in-stalled a flashlight app on it. But unlike most flashlight apps that provide light, this flashlight app forces on the camera on Andrew’s phone. Almost immediately, McAfee receives a photograph on his phone. It is of Andrew’s face.

The room oohs and aahs.

“These apps are not all designed by Google or IBM,” says McAfee. “Some of them are designed by two guys in Korea. We know nothing about these people.”

McAfee then moves into a pitch for his D-Central and D-Vasive apps. The red light flashes, and his time is up. Offstage, he looks depressed. “That audience doesn’t get it or they don’t care.” He looks around backstage. “Well, at least I made 25 grand.” He brightens only when a fat man with a parrot on his shoulder asks for his email. McAfee scribbles down the parrot guy’s email. “I think that guy is the only one here who knows what I’m talking about,” says McAfee.

At the airport, McAfee isn’t selected for further TSA screening. He is perplexed and a little angry. He downs a large gulp of vodka he had poured into a juice bottle. Pool makes a joke.

“John, maybe it’s because you’re too old.”

At dawn, we land in Atlanta, and the six-hour drive to Lexington passes in a haze. The Blazer fills up with cigarette smoke as Pool and McAfee check their arsenal: a Smith & Wesson .40, a .380 Ruger, and another three or four handguns in the front seat. “I like to have a small one in my waistband,” says McAfee. “Sitting on the toilet is a real vulnerable position.”

Pool eyes a fellow driver nervously before gunning the truck out of range. McAfee tells me that when he was fleeing whomever, the safest place at night was parked between two truckers at a rest stop. “Those truckers don’t fuck around.”

The drive goes on, and McAfee promises he will play for me an audio smoking gun: a conversation he taped with John Zabaneh, a shadowy Belizean businessman and known drug trafficker who, McAfee says, admitted that the cartel is after him. I fall asleep to Pool and McAfee singing along to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away.”

The next day, John McAfee welcomes me to his home or, more correctly, the main floor, because the rest of the place is booby-trapped. The dining room table is covered in bullets, a semiautomatic rifle, a pistol, and a handful of burner phones. The Zabaneh listening party is delayed because McAfee wants to walk the property. It’s two hilly acres with plenty of trees, and sunlight slipping through the branches. He tells me to be careful because there are fish hooks strung between trees to lasso intruders. Just last month, he says, two gunshots were fired at his property. Unfortunately, the only ones home were McAfee and a 10-year-old boy who was helping with yard work.

He tells me the cream cheese theory and then pauses underneath a tree, looking at the ground. “See how smooth that is, no leaves? That shows me someone was here and they were dragging something. Now where does this go?” Within minutes, McAfee is on the ground underneath his deck. There’s a slight indentation in the dirt. “They were digging down here, but why? To pump nerve gas into the house, that’d be easy to do.” McAfee lets out a yelp and holds up a copper-colored rock.

“See this rock? It’s from a Mexican village. The cartel guys bring it with them to remind them of home. You won’t find another rock like this on the property.”

Except I do, 50 feet away, a great big pile of copper rocks. McAfee triumphantly holds up a blue lighter. “This lighter is fresh. Now tell me someone wasn’t here.”

I don’t have the heart to tell him that’s his own lighter, which he used to light his cigarette 15 minutes ago. McAfee keeps digging for a half-hour before holding up a fistful of wire. Bob wanders outside at the ruckus. He takes a look at the wire.

“I think that’s just cable wire from the Nineties. Every house has it.”

McAfee looks crestfallen.

“OK, fair enough.”

Sunlight is fading and McAfee looks at his watch.

“Jesus, it’s going to be dark soon. I can’t have anyone over after dark; it’s a security risk. You have to go; we’ll listen to the tapes tomorrow.”

That night I creep my rental car past John McAfee’s property twice, but I don’t see any activity, no spotter in the window, no Mexican cartel dudes eating cream cheese. The next morning, I ring McAfee’s door at 10 am, and despite his dog howling, no one comes. I return a couple of hours later, and there’s no answer, but as I walk to my car I hear McAfee’s voice. He’s in a robe and his eyes are unfocused. He tells me to come in and wait at the gun table while he takes a shower. He reappears, better dressed but still wobbly. It was a rough night. He swears he saw four men outside in the dark but couldn’t get a picture because of the mattresses covering his windows. He charged after them, brandishing a gun. He heard only one voice. It was John Pool.

“Get the hell back in the house!”

McAfee makes us tequila sunrises. I ask him what he thinks his father — who committed suicide when McAfee was 15 — would think of his life. “He would be proud,” says McAfee unsteadily. “But he was an alcoholic and abusive; it would have been better if he’d killed himself sooner.”

I wonder aloud whether his reduced circumstances — Belizean estate to ramshackle home in Tennessee — are real this time or another contrivance. He shrugs and says nothing, offering a Cheshire grin. Then I ask a simple question: Maybe he is too paranoid, while the rest of America needs to be more paranoid?

“Probably true, but you’d be paranoid if you’ve lived through what I lived through,” says McAfee. He takes a long slug from his drink and suddenly looks very old. “America is in a state of somnolence. It’s an avoidance of paranoia through ignoring reality. Mine is an enhanced paranoia, but I may be enhancing reality.”

He then plays the Zabaneh tape. It’s a scratchy recorded cell conversation, in which Zabaneh seems more baffled as to how McAfee got his number, and actually denies having anything to do with the cartel chasing him across the known world.

The tape is inconclusive, like all things McAfee. With Janice gone and Pool sleeping off the night, John is at loose ends. While the D-Central app is free, he admits that the more sophisticated D-Vasive app has been a commercial failure, selling about 5,000 copies at $5.98. But he swears they both will vault to the top of the apps charts as soon as the Russians or the Chinese or the Koreans post those pics of American teens in the shower.

Other cyber-security experts doubt his faith. Jarret Raim at Rackspace brings up an interesting point about last year’s hacking of celebrity nudes. “Most of the ire was at Apple; it wasn’t like, ‘We need to buy McAfee.’ It was, ‘Why the fuck did you let this happen?’ Apple is the big kid on the block; they’re going to fix that.”

In other words, people aren’t likely to run out to McAfee in case of security Armageddon. They’re going to turn to their overlords at Google and Apple to fix things, and fix they will, because they have billions at stake. The best McAfee can hope for is to have his concept bought out.

Just as significantly, other apps are already passing D-Vasive by. Security expert Babak Pasdar estimates there are 25 or so apps that do what McAfee’s do. He told me about a company called CopilotFamily that allows parents to remotely deactivate their kids’ phones if they think they’re interacting with someone dangerous. Still, McAfee trudges on, a not-quite-false prophet without honor. He pours another drink and stirs it with his long fingers. “I’m doing this because people need to wake up,” he says. “If they don’t, I’m going to resign from this society and live in a fucking cave for the remaining years of my life.”

We leave his current cave and drive around town, the same streets where, in August, McAfee will be pulled over for DUI and possession of a firearm while intoxicated. (He’ll blame a new Xanax prescription.) McAfee wants me to meet the police commissioner, who he swears is his friend. But he forgets it’s Saturday and no one is around. It’s time for me to go. McAfee gives me a final warning.

“Be careful: Now that you know me, they’re watching you, too.”

We never did find those cream cheese packets.